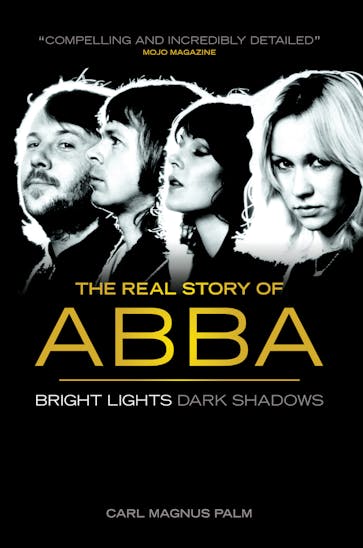

Books about ABBA and related subjects

ABBA biographies, musical examinations and pictorial surveys

Sunday Times review

published April 01, 2010

Sunday Times (UK), September 2, 2001

BOOKS

Mamma Mia! How did Abba do it? And why, 20 years after they split, are they still so popular?

Successful as they were during their professional lifetime, Abba never imagined they would come to be regarded as a kind of kitschy pop religion. Their last-ever performance was an appearance on the BBC's Late Late Breakfast Show in December 1982, where they mimed to a couple of songs and also "endured an inconsequential interview with host Noel Edmonds", as Carl Magnus Palm puts it. In its fatuous way, this was the perfect swansong for the Swedish quartet, whose arrival as winners of the 1974 Eurovision Song Contest consigned them forever to the mums-and-pre-teens graveyard of light entertainment and ensured that they would never enjoy any serious respect from critics.

But what a difference a decade makes. The compilation album, Abba Gold, was released in 1992 and has sold 20m copies worldwide. The stage musical Mamma Mia!, a batch of Abba hits strung around a flimsy approximation of a plot, has become an international smash, following in the wake of the Abba-idolising movies The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert and Muriel's Wedding. The likes of Bono, the Fugees, Elvis Costello, Pete Townshend and even the late Kurt Cobain have all declared their admiration for Abba's timeless pop genius.

The Abbanauts themselves are too old and wise to take all this with anything other than a lorry-load of salt. "Is there no-one who can come up with any new stuff, who can do something corresponding to what we did back then?" wondered Benny Andersson recently. "Isn't it kind of empty when the greatest success is generated by something that was made 20 years ago?" Palm would agree, noting that Stockholm's latest pop phenomenon, writer and producer Max Martin (the mastermind behind Britney Spears and the Backstreet Boys), is a faceless back-room boffin who offers none of the human drama that underpinned Abba's massive appeal.

Palm's book achieves the difficult feat of capturing the multiple layers of Abba - as individuals, as two married couples, as a showbusiness phenomenon and a commercial enterprise - with a deftness unusual in a rock biography. His prose doesn't exactly fizz off the page, but it's lucid and unpretentious, avoiding the hysteria and shoddiness that have brought the genre into disrepute. He knows his material is gripping enough to need little embellishment. The story of Anni-Frid "Frida" Lyngstad's upbringing in exile in Sweden with her grandmother, traumatised by the stigma of being the illegitimate child of a Norwegian mother and a sergeant in Hitler's occupying Wehrmacht, would tickle the tragic taste buds of an Ibsen. Agnetha Fältskog's neurotic withdrawal from public life following Abba's demise, and her disastrous relationship with an obsessive fan, read like a classic fable of the price of stardom.

The author also benefits from the fact that his subject matter is off the usual Anglo-American music business track. Instead of the over-familiar litany of Liverpool, swinging London and southern California, Palm is able to introduce us to the mysterious hinterlands of Swedish folk and schlager music, in which the future members of Abba took their first hopeful steps.

For instance, the young Björn Ulvaeus first became known to Swedish audiences for his work with the Hootenanny Singers, singing Swedish traditional songs and touring the country's "folkpark" circuit. Meanwhile, Anni-Frid - "the songbird of Eskilstuna" - was singing jazz standards with Bengt Sandlund's big band, Agnetha was a naive but determined aspiring singer-songwriter, and Andersson was playing keyboards in a pseudo-American rock'n'roll band called The Hep Stars.

Pivotal to the story is the band's manager and business brain, Stig Anderson, who signed Björn to his fledgling Polar record company as early as 1963. Stig's rags-to-riches background, bullish business deals and habit of getting drunk and sacking all his employees at night and then rehiring them the next morning made him a legend in Sweden, and he barges his way through these pages like an overbearing mixture of Colonel Tom Parker, Richard Branson and Mohamed al-Fayed. Although based in the record-business backwater of Sweden, the ambitious and energetic Anderson had built up an extensive network of international contacts in music publishing, which he used to put together advantageous record deals for Abba. Avoiding the usual route of signing up to a single multinational company, Anderson took the more demanding but more rewarding course of hand-picking the most suitable labels in different territories, ensuring that Abba releases were always given priority treatment.

It is Palm's skill in linking the parochial and often bizarre world of Sweden and its music industry to the grander world picture which gives his book its driving force. While it's sobering to be reminded of the contempt in which Abba's brilliantly frothy pop songs and ridiculous stage costumes were originally held in many quarters, including the high-minded British music press, it's startling to discover the extent of the hostility to them in their homeland. As the group churned out the likes of Waterloo, SOS and Dancing Queen, and the Abba-Stig Anderson empire accrued ever greater wealth, they ran into a ferocious backlash from the so-called Music Movement, or "progg", a left-wing, anti-capitalist tendency that deplored the slick commercialism that Abba exemplified. This hostility went so far that musicians who worked with Abba were banned from performing in venues controlled by the Music Movement.

But Palm also tolls a funeral bell for the idealistic, socially cohesive Sweden of the 1970s. The 1990s brought recession, monetarism and the demolition of the country's prized welfare system. Perhaps the Abba revival was prompted by a nostalgic yearning for the happier times evoked by the quartet's pop anthems. "As Benny has opined, the basic intention to make the world a better place was honourable," he writes. "If only it hadn't been accompanied by such a judgmental and insulated world-view at the time." Palm has ensured that the view is now a lot clearer.

Order from

- Amazon.com (US)

- Amazon.com (Kindle edition, US)

- Amazon.co.uk (UK)

- Amazon.co.uk (Kindle edition, UK)

- Amazon.de (Germany)

- Amazon.fr (France)

- Adlibris (Sweden)

More info

- Back and front of cover

- Facebook page for the book

- Reader reviews (2014 edition)

- The Birth of Frida (excerpt from 2014 edition)

- Editor Chris Charlesworth blogs about the book

- icethesite story about the 2014 edition

- Original 2001 edition of the book

- Journalist Richard Williams blogs about the book

- TV interview about the book

- The Guardian's Valentine's Day reading Top Ten

- Long-time fan Ian Cole on the book

- Review extracts (print media and radio)

- Reviews and interviews in full (print media and radio)

- German version of the book

- Russian version of the book

- Audio book version

ABBA

BooksStudio albumsCompilations and box setsDVDsSolo projectsGuided tour of ABBA's StockholmABBA lectureMore ABBA© 2003–2025 Carl Magnus Palm. All rights reserved. Produced by Disco Works